Enrichment Program Implementation to Modify Stereotypic Behavior of Captive Polar Bears at the Central Park Zoo

Laura Venner, Columbia University, Department of Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology

Yula Kapetanakos, Central Park Zoo/WCS

Prof. Stephanie Pfirman, Barnard College

May 1, 2006

Abstract

Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) are often among the animals exhibited at zoos. However, visitors of polar bear exhibits often observe the polar bears performing repetitive, and seemingly pointless, behaviors instead of the natural behaviors that are witnessed in non-captive polar bears, such as hunting and resting. In captivity, polar bears often engage in stereotypic behaviors such as pacing and rocking for reasons that have yet to be determined by scientists. Many zoos are beginning to implement enrichment programs in an effort to understand and reduce the stereotypic behaviors witnessed in their captive polar bears. The enrichment programs are designed to stimulate and increase the level of activity of the zoo’s polar bears in an effort to keep the polar bears engaged in activities other than stereotypies which are categorized as undesirable behaviors.

The Central Park Zoo is conducting a study of the two captive polar bears it currently exhibits and their respective stereotypic behaviors. The study is being performed to reveal the effectiveness of their polar bear program which consists of food enrichment, non-food enrichment, training, and exhibit modification. To discern the effectiveness of the program, records of each polar bear’s daily activities, also known as activity budgets, are being collected. Preliminary results infer that the enrichment program is beneficial at minimizing the stereotypies witnessed in the Central Park Zoo’s polar bears since their arrival at the Zoo in 1988. The data indicate that Ida, the female polar bear, and Gus, the male polar bear, spend less than 10% of their time engaged in stereotypic activities. In addition, the data showed that at the onset of breeding season in February, Ida’s enrichment use increased dramatically and Gus’s stereotypic behavior increased as well. Further analysis of the data for the month of February revealed that the increases in the polar bear’s activities occurred simultaneously on the 4th of February. This drastic spike in the polar bear’s respective behaviors should be analyzed in future studies to determine the cause or causes for the increase. Hormonal changes in the month of February should be scrutinized to determine if one or both polar bears are releasing a chemical signature that causes them to drastically increase their activity levels.

The results of this study will be used to create a proposal for future studies at the Central Park Zoo that may enable managers of captive polar bears to refine their enrichment programs and further minimize the time their polar bears spend stereotyping. Some recommendations that are being put forward include carefully monitoring the polar bears inside their dens and outside in the exhibit. I also suggest that a procedure that introduces the various enrichment items in a controlled fashion be established. It may also be beneficial to separate the polar bears to determine if the polar bears are having a negative, positive or no effect on their own and each other’s enrichment use and stereotypic activities.

Introduction

Identifying the problem

Stereotypic behaviors are exhibited by many captive species in zoos (Clubb, 2004). These behaviors include, but are not limited to, repetitive actions such as tongue flicking, water pacing, land pacing, head-swinging, refusal of food, eating vomit and prolonged periods of resting. Repetitive behaviors are often viewed as disturbing by zoo visitors and keepers alike as such behaviors conclude with no functional end result and therefore appear obsessive. Stereotypic behaviors are not exhibited by wild polar bears but are prevalent in their zoo-kept counterparts and it has been suggested that polar bears, as well as other animals, are driven into some type of psychosis as a result of their captivity which causes them to stereotype (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., 1992; Mason, 1991; Wechsler, 1991). Today, zoos are more responsible and sensitive in their approach to captive animals, with conservationists and scientists involved in helping zoos focus on conservation and education. In the past, zoos kept wild animals inside small cages with cement floors but today many zoos exhibit their animals in more natural settings to help the public understand the importance of habitat and species conservation. This serves a dual purpose as visitors to zoos seem more interested in the exhibits when the animals appear to be healthy and content in their environment, and the animals are no longer in small cages (Coe, 1985). But, in the limited exhibit areas of zoos, large animals such as polar bears still do not seem to have enough space, so artificial stimulation is being introduced in an effort to help them live richer lives that are filled with diversity (Altman, 1991; Grandia et al., 2001). Many zoos are moving beyond merely enhancing habitats and are trying to motivate their captive animals to engage in behaviors that are more productive. Enrichment programs that utilize artificial stimulation and food enrichment, among other techniques, are being implemented in an effort to initiate this motivation and help captive animals display the wild behaviors that are typical of their species rather than spending time on stereotypic behaviors that are not displayed by their wild counterparts.

Enrichment program need and effectiveness

In addition to polar bears, behavioral similarities exist between other captive bear species such as brown (Ursus arctos), American black (Ursus americanus), kodiak (Ursus arcios), sloth (Melursus ursinus), Asian black (Ursus thibetanus) and spectacled bears (Tremarctos ornatus) as well as giant pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) (Altman, 1999; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., 1992; Grandia et al., 2001; Swaisgood et al., 2001). These bears engage in similar stereotypic behaviors as polar bears, when placed in captivity. For instance, a study involving the sloth and American black bear was conducted to try to reduce the land pacing activities of the bears. The study focused on the introduction of honey filled logs and how interest in those logs might reduce the stereotypic behaviors witnessed by the keepers (Carlstead et al., 1991). The bears were engaging in the same type of stereotypic behavior as Ida at the Central Park Zoo and similar methods were being introduced by the bear’s managers to try to discourage the stereotypic land pacing of their sloth and American black bears. These behaviors are not only witnessed in captive bears but in other species as well. Elephants are a good example of a captive species that spends a great deal of their activity budgets performing stereotypic behaviors. Like polar bears, elephants in captivity rock or sway back and forth. However, the challenges faced in devising enrichment items for elephants are difficult as elephants do not have the ability to consistently pounce on and throw objects such as polar bears do. Elephants also lack the ability to dig aggressively or to open tightly sealed drums so different enrichment items have to be tailor designed for the unique physiology of elephants. An enrichment device was suggested in a study involving elephants that mimics wild elephant behavior. Scientists looked at the simple wild elephant behavior of shaking trees to obtain fruit and tried to imagine a design for a device that would enable captive elephants to engage in that behavior. The scientists proposed a device called a “wobble tree” that would allow elephants to shake and push the devise subsequently triggering fruit or other food items to be released from a dispenser located at the top of the wobble tree beyond the reach of the elephant’s trunk. Although this device seems intuitive, it has not been created yet as the material the device is made from must be able to withstand the force of an elephant pushing up against it without the device toppling over or snapping it in two (Law and Kitchener, 2002). Stereotypic behaviors are not specific to polar bears and the importance of discovering successful enrichment programs and items that can be incorporated into the captive environments of many species is essential in order to maintain healthy breeding animals in our zoos. Minimizing stereotypic behaviors will also enable scientists to observe natural behaviors in their captive animals which will subsequently aid larger conservation efforts for the captive animal’s wild counterparts (Altman, 1999; Carlstead et al., 1991; Clubb, 2004, Coe, 1985; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., 1992; Grandia et al., 2001; Swaisgood et al., 2001). Refining enrichment programs to make them as productive as possible can enable scientists to gain a better understanding of a species which may subsequently lead to species survival in captivity and conservation in the wild. It is important to note that a species consists of individuals and each individual in a species may display unique stereotypic behaviors as well as unique responses to enrichment efforts.

Enrichment program designs

There are several approaches that can be used in enrichment programs but food enrichment is viewed as one of the most important because eating is such a stimulating activity for polar bears. Food enrichment in zoos include multiple feedings, hiding food, smearing food such as peanut butter on the exhibit space or non-food items, and freezing food inside of ice blocks. In addition, tossing food into the exhibit at random times also serves to add diversity to the food enrichment program (Ames, 1993; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., 1992; Wechsler, 1991). However, food enrichment only occupies the attention of the polar bears for the length of time that it takes for the food to be consumed (Altman, 1999). This creates a significant problem as keepers cannot continuously feed the polar bears in their care and the polar bears soon resort to less desirable behaviors, such as pacing, to occupy their time shortly after the food enrichment item has been consumed. In light of this, non-food enrichment items have also been employed which range from natural items such as browse (leafy twigs, shrubs and similar items) to manmade items such as plastic drums and buckets.

Central Park Zoo

At the Central Park Zoo, the exhibit animals were housed in standard stock cages until the re-opening of the zoo in 1988 under the management of the Wildlife Conservation Society. The exhibit spaces were redesigned to mimic the animal’s natural habitat as closely as possible. The polar bear exhibit that was installed at the zoo consists of an irregularly shaped gunnite (very strong waterproof concrete) bowl with a filtered pool. The rock work inside the exhibit was designed to offer a visual separation for the polar bears housed within (Lyles et al., 1997). Two polar bears currently reside at the Central Park Zoo in New York City, a female named Ida and a male named Gus. Both polar bears were born in captivity and are approximately 18 years old. According to anecdotal evidence, acquired from the senior keeper, Gus began his stereotypic water pacing behavior shortly after arriving at the Zoo in 1988. Ida’s land pacing began shortly after Gus’s pacing was observed. There was also a third polar bear in the exhibit named Germany (also known as Lily). Germany was a female who developed liver cancer and was euthanized in 2004. The head keeper reported that when Germany disappeared from the exhibit, Gus and Ida’s stereotypic behavior increased dramatically with Gus water pacing for most of the day and Ida spinning repeatedly or “hamster wheeling” in the water. In an effort to decrease the drastic stereotypic behaviors performed by the polar bears during this period of stress, the keepers reported that they increased the number of enrichment items in the exhibit and introduced novel items more frequently until the stereotypic behaviors resumed at a pace witnessed prior to the death of Germany. Following this stressful transition period, Ida and Gus’s stereotypic behaviors appear to have decreased significantly from the reported levels witnessed by keepers prior to the implementation of the current enrichment program.

Ida’s stereotypic behavior is rarely the focus of Zoo visitors. Visitors to the Central Park Zoo have focused primarily on Gus’s behavior. His water pacing takes on repetitive movements that seem unusual to a lay person but are in line with the behaviors witnessed among other captive polar bears (Ames, 1993, Wechsler, 1991). Gus swims a regular pattern where he begins with a rocking motion at one end of the pool near the dens before entering the water. After entering the pool he comes up out of the water and begins to float on his back. He propels himself by pushing off from a point on the rock exhibit, flicks his tongue, and then pushes off from two more points on the rock exhibit before he approaches the underground viewing window where he turns around and begins the process again. Each time Gus cycles through his behavior pattern, he touches the rock exhibit at the same three points.

Figure 1. Gus water pacing while Ida remains alert and still by the den entrance after a bout of land pacing June 20, 2005).

Captive animals, and polar bears in particular, often perform the same styles of stereotypic movements. There are polar bears that exhibit the same type of stereotyping that Gus displays and some that exhibit the same type of stereotypic behavior that Ida displays. Many polar bears land pace with a fixed number of steps taken each time, or water pace in a circular motion in the exact same part of their enclosure (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., 1992; Mason, 1991; Wechsler, 1991). Once a polar bear establishes a stereotypic behavior, the polar bear is resistant to any modification of that behavior. However, it has been suggested that stereotyping is a learned behavior as this behavior is not witnessed in young or wild polar bears and these behaviors may be altered or eliminated in captive polar bears if the correct enrichment formula is developed early on in the behavior’s development (Ames, 1993). Developmental behaviors of captive polar bear cubs reveal that management and manipulation of environmental conditions and conditioning procedures influence the patterns of behavior exhibited by polar bear cubs and, depending on the modification, behaviors are altered as a result of this intervention (Ames, 1993, Greenwald and Dabek, 2003). The initiation of a formal enrichment program at the Central Park Zoo did not occur until 1994 when Ida, Gus and Germany (also known as Lily) were already mature polar bears. Germany died in June of 2004 prior to the commencement of the current study being conducted and referenced herein therefore this study cannot report on Germany’s influence on the stereotypic behaviors of Ida and Gus. However, the zoo has reported that the current enrichment program has resulted in a marked decrease in Ida and Gus’s stereotypic behaviors which were witnessed by the keepers and staff both prior to and after Germany’s death.

Causes of stereotypic behavior

Previous research elucidates the causes of stereotypic behaviors in captive polar bears (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Grandia et al., 2001; Grittinger, 1997; Mason, 1991; Swaisgood et al., 2001; Wechsler, 1991). A lack of stimulation and diversity in the exhibit space is one cause of the stereotypic behaviors witnessed in captive polar bears. If a zoo exhibit is devoid of novel items the polar bears may become bored. In the wild, polar bears cover a wide area when searching for food and encounter a host of novel items as well as scents and surroundings (Hansen, 2004). In a zoo exhibit, the surroundings change very little and if the same enrichment items are introduced or left in the exhibit then the polar bears may not be interested enough to interact with the items. The need to occupy time foraging and hunting is eliminated as well in the captive environment which leaves many hours open for the polar bears to engage in undesirable stereotypic behaviors (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Carlstead et al., 1991; Grandia et al., 2001, Wechsler, 1992).

The lack of range is another area of concern when designing captive habitats for polar bears in zoos and might explain some stereotypic behaviors as well. The circumpolar Arctic range of polar bears allows for a great deal of movement and novel stimulation as well as hunting, diversity and open space. Polar bears have been observed migrating several hundred to several thousand kilometers in the wild. In a study comparing the movements of male and female polar bears in the wild it was discovered that males and females traveled large distances each month. Males traveled an average of 387 km/month and females traveled between 217 and 302 km/month. The average monthly activity-area size for the male polar bears was 8541 km2 while the average monthly activity-area size for the female polar bears averaged between 3698 and 10,585 km2 (Amstrup et al., 2001). Constructing an area large enough to mimic the natural environment of polar bears is not a possibility in zoo exhibits (Hansen, 2004). The differences in the time allotted to stereotypic behaviors between male and female polar bears may result from the polar bear’s natural roaming capacity, with regard to the polar bear’ s relative size, being limited. Male polar bears are larger than female polar bears which may contribute to the stereotypic behavior differences between Gus and Ida as well. Gus is larger than Ida weighing approximately 1000 pounds compared to Ida’s average weight of approximately 640 pounds.

Polar bears are not generally social animals and the vast area of their natural habitat allows the polar bears to establish enough distance between each other to avoid confrontation. Captive polar bears are unable to avoid confrontation with their exhibit mates in the small confined area of a zoo exhibit which may lead to stereotypic behavior as well. (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Amstrup, 2001; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; LexisNexis, 1995; Stirling and McEwan, 1975; Taylor et al., 2001; Wechsler, 1991, Wechsler, 1992).

Others see the stereotypic behaviors of polar bears as resulting directly from frustrated appetitive behavior. Foraging is a major part of a wild polar bear’s daily activity budget. In the wild, seasonal changes cause differences in food availability and polar bears are forced to travel and hunt to find their food. In the wild, a polar bear’s meals are eaten at unpredictable times but in captivity, polar bears are fed prepared food at regular times. It has been suggested that providing food to captive polar bears in mundane and predictable ways results in a lack of motivation to eat. When food is given at unexpected times and in unexpected ways, the motivation and concentration given to the finding and consumption of the food is heightened (Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Wechsler, 1991). Polar bears also have an acute sense of smell and smelling food that they cannot obtain from other exhibits and zoo cafeterias may increase their frustration and stereotypic behavior as well (Altman, 1999; Ames, 1993; Carlstead et al., 1991; Fischbacher and Schmid, 1999; Forthman et al., Grandia et al., 2001, Stirling and McEwan, 1975, Wechsler, 1991, Wechsler, 1992).

Approach / Methods

Data collection

Instantaneous scan sampling (Altmann, 1974) was performed between the hours of 9:30 and 16:30 and each polar bear’s behavior was recorded at three minute intervals during 2 – 4 hour sessions, twice per day (Appendix A). This is considered an event recording as the instantaneous behavior is looked at rather than the behavior over a period of time (Altmann, 1974). An instantaneous scan sample ethogram was employed to record the data (Appendix B). The ethogram contains eight behavioral categories that enable the data recorders to maintain consistency in their observations. The eight categories used by the Central Park Zoo are as follows: resting, alert and still, movement, stereotypes, enrichment use, social-positive, social-agonistic, and other. Within each category subcategories exist that further define the behavior of the polar bears (Appendix B). For example, if Gus was moving at the instant of recording, one of the following subcategories would be recorded on the data sheet in the movement column: the number 1 would be recorded if Gus were walking, 2 if he were climbing, 3 if he were swimming, and 4 if he were diving. Ethograms enable data collectors to record their data in a uniform manner based on criteria set forth at the initiation of the study.

In addition, focal sampling of enrichment item use was collected on separate data collection sheets (Appendix C). Each enrichment item and the time spent on that item was observed and incorporated as part of the data set. A list of enrichment items introduced to the polar bears by the Central Park Zoo was developed so that data collectors could identify the items consistently (Appendix D). Other information was also recorded on the data collection sheets such as approximations of the weather and visitor attendance. The observations of Ida and Gus commenced on December 1, 2004 and concluded on January 31, 2006.

Anecdotal evidence is also being referenced in the Central Park Zoo study but will not be incorporated in the analysis of the data. Data was not collected prior to or at the initiation of the current enrichment program at the Central Park Zoo so reliance on anecdotal evidence is necessary to establish that changes in the stereotypic behaviors of the polar bears has indeed occurred. The keepers report that prior to the initiation of the formal enrichment program Gus spent most of his day engaged in stereotypic water pacing in the pool while Ida spent most of her day land pacing by the dens.

Enrichment Items

The enrichment items used by the Central Park Zoo include food enrichment items, non-food enrichment items, exhibit modification and training. Some food enrichment items include, but are not limited to: scattered food, frozen and live fish, peanut butter and honey smeared onto non-food items and frozen treats such as fish, vegetables and fruit inside of ice blocks (Appendix D). Non-food enrichment items include: simple containers such as rubber buckets and barrels, and more complex containers such as puzzle boxes as well as fire hoses, browse and cardboard boxes (Appendix D). The exhibit was modified to include gravel beds where food can be hidden and buried, an ice machine and misters. The keepers also have brief training sessions with the polar bears at which they are rewarded with food for performing small tasks such as giving their paws, opening their mouths and touching a target with their noses and entering their dens on command.

Figure 2. Gus being rewarded with Omnivore chow and carrots after successfully being gated (left). Target used for training Ida and Gus. Ida and Gus touch the target with their paws and noses and are subsequently rewarded with food treats (center). A list of food items given to Ida and Gus throughout the day (right). (July 15, 2005).

Results

Activity budgets and data analysis

Ida’s stereotypic behavior consists mostly of land pacing by the dens and seems to increase when she is agitated by weather conditions or when she is hungry. She has been observed to pace more frequently by the dens when the rain is very heavy or when the humidity and temperature outside are high. In addition, when keepers reported that Gus ate Ida’s food inside the dens or when Gus consumes most of the treats in the exhibit, Ida seems to become agitated, perhaps by hunger, and starts to land pace near the dens. A good deal of attention has been placed on the stereotypic behavior of Gus by visitors to the Central Park Zoo. There is even a small book dedicated to Gus’s life in New York City written by Henry Beard and John Boswell entitled, What’s Worrying Gus?: The True Story of a Big City Bear (1995). The cover of the book displays a picture of Gus lying on a couch in a psychiatrist’s office with a view of New York City in the background.

Figure 3. Cover of book, Beard, Henry and John Boswell, What's Worrying Gus?: The True Story of a Big City Bear. New York: Villard, November 21, 1995.

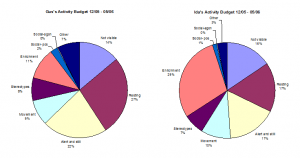

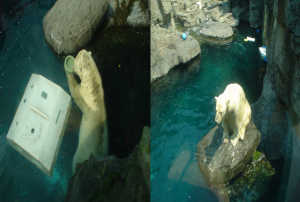

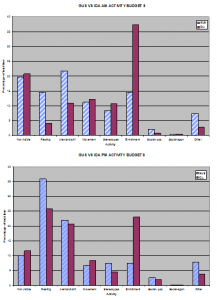

Based on the instantaneous scan sampling, Gus’s situation does not appear as dire as the authors of the book express (Figure 3). Stereotyping not only takes up a smaller percentage of the total time of the polar bear’s activity budgets than was expected, but it is not even a major consumer in the activity budgets of Gus or Ida (Figure 5). Gus’s activity budget consists largely of resting and being alert and still with his enrichment use being the third highest recorded value. Ida’s budget consists mostly of enrichment use with resting and being alert and still having nearly equal values. Overall, behaviors other than stereotypies take up a larger percent of the polar bears daily activity budgets with stereotypies taking up less than 10% of each polar bear’s activity budget (Figure 5). The category representing “not visible” indicates recorded observations during which the polar bears were either gated or simply out of view of the observer as the observing station was situated in one specific location outside the exhibit area. Many times Ida was not visible from the observation point but could be seen by walking to the polar bear viewing window where she was alert and still watching the visitors and the polar bear kitchen door in anticipation of food enrichment (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Ida alert and still at the polar bear viewing window near the polar bear kitchen. This behavior would be recorded as “not visible” as the location of the observers was above this region. (June 30, 2005).

Figure 5. Activity budgets for Gus and Ida for December 1, 2004 through May 1, 2005

Ida interacts with enrichment 26% more than Gus does (Figure 5). Ida uses the enrichment devices to mimic wild behaviors as well. She is often observed pounding on the ice float/puzzle boxes for extended periods which is indicative of wild polar bear behavior. Wild polar bears exhibit the same behavior when they are trying to break open seal dens. In addition, Ida took the large barrels filled with water out of the pool and pounced on them with her front paws until most of the water was expelled. She would then lift the barrel up with her two front paws, toss the barrel into the water and dive into the water after the barrel. Once the barrel was in the water she would float on her back and cradle the barrel in her arms resting it on her stomach just as she would rest her prey on her stomach in the wild after making a kill.

Figure 6. Ida and Gus interacting with various non-food enrichment devices. After pounding a red barrel into a rock crevice in the exhibit, Ida interacts with a blue barrel (left). Gus is pictured here, on the right, trying to retrieve various enrichment items from a puzzle box/ice float device (May 27, 2005).

Figure 7. Gus is pictured here interacting with a food enrichment item. He is licking peanut butter from a bowl which he retrieved from the puzzle box/ice float by his side (left). Ida, pictured on the right, is exhibiting an alert and still behavior (June 30, 2005).

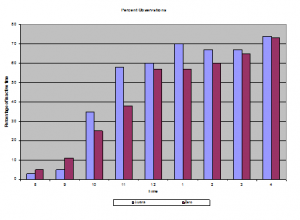

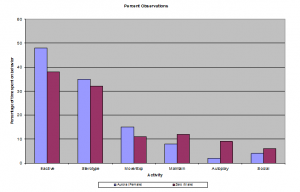

In addition, Ida and Gus are alert and interact more with enrichment in the morning while the afternoon hours find the polar bears engaging in resting behaviors (Figure 8). Other studies have resulted in similar data that also show polar bears decreasing their activity levels as the afternoon hours approach (Altman, 1999; Grittinger, 1997; Swaisgood et al., 2001). At the Milwaukee zoo, two polar bears, Aurora and Zero, were studied in a similar fashion to Ida and Gus. Aurora is a female and Zero is a male polar bear that, at the time of the study, were living together for four years. Instantaneous scan sampling was used at one-minute intervals during 20 minute sessions recording the location and activity of the polar bears. Data derived from that study (Figure 9) shows that Aurora and Zero also exhibit higher levels of activity in the morning with their activity levels decreasing as the day progresses (Grittinger, 1997).

Figure 8. Gus and Ida’s AM vs. PM activity budget show that the polar bears are more active in the morning and tend to rest more in the afternoon.

Figure 9. Percentages of inactive time for Aurora and Zero at the Milwaukee Zoo. Numbers are estimated from “Activity patterns in polar bears at the Milwaukee County Zoo,” (Grittinger, 1997).

Seasonal variations

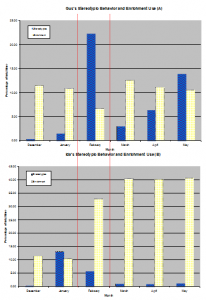

The enrichment and stereotypic activities of the polar bears have been isolated from the rest of the behaviors and are illustrated in Figure 10. Gus’s enrichment use is fairly consistent with a drop in enrichment use in February. His stereotypic behavior follows an upward gradient that shows an increase in stereotypic behavior in the month of February before decreasing in March and following an upward gradient. Ida’s behaviors are the opposite displaying a sizable increase in enrichment use in February while her stereotypic behavior follows a mostly downward gradient.

Figure 10. Gus (A) and Ida’s (B) activity budgets with respect to stereotypic activity and enrichment use.

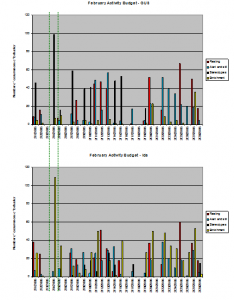

An area of interest in the data is the sizable spike in Ida’s enrichment use in the month of February which then increases slightly and is subsequently maintained. Gus’s enrichment use is relatively level throughout the six months. This large spike in Ida’s enrichment use is unexplained and warrants further investigation into the causes of Ida’s increased enrichment use. Since February represents the onset of the breeding season, Ida may be attempting to avoid Gus’s advances by keeping herself busy with enrichment items in an effort to deter his attention (Figure 11). Upon further manipulation of the data for February, it was discovered that Ida and Gus not only increase in their respective behaviors in February but do so on exactly the same day of February 4, 2005 (Figure 12). After February 15, Gus’s stereotypic behavior seems to subside however, Ida’s excessive enrichment use continues throughout the month although not as aggressively as on February 4, 2005 (Figure 12).

Figure 11. Ida interacting with food enrichment while ignoring Gus’s advances (June 20, 2005).

Figure 12. This figure displays the four primary behaviors of Ida and Gus in the month of February. As can been seen in the graphs, increases in stereotypic behavior in Gus and in enrichment interaction in Ida occur on the exact same day of February 4, 2005.

Discussion

The data, reflecting data collection from December 2004 through May 2005, (Figure 5) reveal that both Ida and Gus spend more time engaged in activities other than stereotypies with both polar bears engaging in stereotypic behavior less than 10% of the observed time. In a similar study done at the Milwaukee County Zoo, the stereotypic behaviors of two captive polar bears, a male named Zero, and a female named Aurora, took up 30% of the activity budgets of the polar bears (Grittinger, 1997) after initiation of their enrichment program (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Activity budgets for Aurora and Zero at the Milwaukee Zoo. Numbers are estimated from “Activity patterns in polar bears at the Milwaukee County Zoo,” (Grittinger, 1997).

In the Milwaukee study, the female polar bear, Aurora, engages in stereotypic behavior a bit more than the male Zero but not enough to cause concern (Figure 13). By contrast, Ida interacts with enrichment 26% more than Gus does at the Central Park Zoo (Figure 5).This is an area of the data that needs further analysis to discern why the difference in enrichment use is so substantial between Ida and Gus. An assumption has been made by other studies that the plastic drums and barrels represent “model prey” and are therefore treated as prey by the polar bears (Altman 1999). Ida exhibits more “model prey” behavior when interacting with the enrichment items such as pounding on drums and floating on her back while holding enrichment items (Figure 14). The diversity of objects, although unnatural, appears to encourage these “model prey” behaviors in Ida but not in Gus. Perhaps the food enrichment program is not suited to Gus and causes him to avoid treating the enrichment items as prey or perhaps the objects are not perceived as prey items by Gus. Further studies need to be conducted to evaluate the reason why the “model prey” behavior is more evident in Ida than Gus.

Figure 14. Ida displaying “model prey” behavior. Ida floats on her back holding her “model prey” which, in this case, is a jar with honey inside (left). Ida pounces and crushes a barrel as she would pounce and crush a seal den while hunting (right). (July 1, 2005).

In addition, the times that the polar bears interact with enrichment vary. Gus and Ida’s activity budgets show that they rest more in the afternoon and are alert and active in the morning (Figure 8). A program could be tailor designed to accommodate the polar bear’s active hours. Gus and Ida’s favorite items could be introduced only during the hours that they are alert and active rather than keeping the items in the exhibit all day. In this way, Gus and Ida may anticipate the introduction of the items and be stimulated by them more as they are not always available inside the exhibit. Perhaps, the polar bears would come to associate certain times as “play times” if the enrichment items were only introduced during particular hours and this may lead to fewer stereotypic behaviors.

Conclusions

This research will help zoo officials manipulate their enrichment programs to eradicate or reduce stereotypic behaviors among captive polar bears. This is of great importance since polar bear habitats are diminishing significantly (Derocher et al., 2004, Ferguson et al., 2000). Maintaining healthy breeding polar bears in the zoo environment is important for the successful maintenance of the species. In February, the interaction between Ida and Gus is clearly one of avoidance. As Gus approaches Ida, Ida begins to aggressively interact with enrichment items and avoids Gus’s advancements. This behavior is not conducive to breeding and should be evaluated to discover the reason or reasons why this avoidance occurs.

In addition, if stereotypic behaviors may be stymied or altered before they develop into set patterns through the initiation of managed modification and conditioning procedures and the introduction of enrichment items early on in the captivity of polar bear cubs, then every effort should be made to establish enrichment programs within zoos as early as possible (Ames, 1993, Greenwald and Dabek, 2003). By studying the current population of polar bears in captivity and their reactions to various enrichment programs, methods may be devised that can identify and stall the stereotypic behaviors expressed by polar bears thereby maintaining well adjusted and healthy breeding pairs. Many factors must be looked at in order to provide captive polar bears with successful enrichment devices and more research needs to be conducted in this area to determine which conclusions will garner the most support (Ames, 1993). The recommendations of this thesis may offer variants to the current polar bear enrichment program at the Central Park Zoo and, in doing so, provide the Zoo with methods to conduct a more comprehensive study of Gus and Ida’s stereotypies and enrichment use.

Recommendations

Recommendations can be made that will aid the keepers in recognizing which enrichment methods minimize stereotypic behaviors most efficiently and consistently in captive polar bears (Wechsler 1991). This research can be added to the body of knowledge currently available regarding the stereotypic behaviors of captive polar bears in an effort to determine which enrichment programs are truly effective in minimizing the stereotypic behaviors of polar bears. This research can also be referenced to gain an understanding of the captive behaviors of other species as well and improve enrichment programs currently being conducted at the Central Park and other zoos.

It would be helpful if the keepers at the Central Park Zoo were informed of the scientific approach with regard to conducting research and maintaining accurate records. With this knowledge in hand, the keepers could interact with the scientists observing the stereotypic behaviors of the polar bears to create a better schedule for the introduction and monitoring of enrichment items and use. The data collected to date were recorded without a regimented enrichment item insertion process. The keepers had their own enrichment item preferences which changed daily. The enrichment items that were inserted were not controlled and therefore, the reasons for Ida’s increase in enrichment use cannot be ascertained. It will benefit future studies if the keepers and data collectors maintain a log of which enrichment items are inserted into the exhibit and at what time of day the insertions take place. The log does not have to be complicated and can merely be a notebook that has columns for time, type of enrichment introduced, where the enrichment was introduced into the exhibit or den and the method of introduction. This thesis recommends that each keeper log the enrichment items and methods they allow and use in the exhibit and den areas so that comparisons can be made that might suggest if Ida and Gus’s responses are to one item or to a combination of items and/or stimuli. This type of control would encompass food enrichment as well. Logs recording where food is scattered and hidden in the exhibit and what foods are spontaneously tossed into the exhibit and at what times would be beneficial in understanding which food enrichments introduced were having the best impact on the stereotypic behaviors of the polar bears. Minimizing the extraneous variables, with regard to the enrichment item introduction and presentation, would allow for better control over the behavioral study of Ida and Gus and may help explain the sudden interest in the enrichment items expressed by Ida during the month of February and the following months as well.

Based on these observations, this proposal recommends controlling the introduction of items and logging the specific wild behavior being displayed. For instance, when Ida is pounding on a barrel or ice float/puzzle box the wild behavior exhibited should be noted as prey interaction or breaking into seal den behavior. This would help to isolate the wild behaviors most commonly invoked by the enrichment items and would allow for the items to be tailored to the polar bear’s most common behaviors. If Ida prefers to exhibit pouncing behavior similar to breaking into seal dens, perhaps novel enrichment items could be created to mimic seal dens more effectively keeping her more engaged in that behavior and less engaged in stereotypic activities. Currently, Ida pounces on barrels that can be crushed and plastic puzzle boxes/ice floats that cannot be crushed. A novel item such as a puzzle box/ice float made from ice could be created that would have frozen food items inside of it such as a salmon, shank and apples. The item could be placed in a section or various sections of the exhibit where Ida can pounce on it against a surface that will aid in her breaking the ice block open and retrieving the contents inside the block. At the moment small frozen treats are offered to the polar bears inside of boomer balls (large hard plastic balls) that have been cut in half. However, pouncing is not required to retrieve the contents of the boomer ball frozen treat. After pouncing the novel item and retrieving the food inside, the large block of broken ice would also serve as an enrichment item and a coolant for the water in the pool.

Observing the den behaviors of Ida and Gus may also shed light on their variable enrichment use and stereotypic behaviors. Recording their behaviors inside the dens and then again when the polar bears are released into the exhibit would make the data more comprehensive as something within the den environment could stress the polar bears causing them to engage in stereotypic behaviors when they return to the exhibit area. It may be beneficial to have the data collectors shadow the keepers while they maintain the polar bears. When the keepers are in the exhibit, the recorders could monitor the activities of the polar bears in their dens.

Another recommendation would be to separate the polar bears on certain days and test the enrichment item use of each individual when the partner bear is not a distraction. Observing each polar bear’s reaction to the enrichment items with and without the other polar bear present may lead to a better understanding of the impact that the small exhibit space is having on the stereotypic behaviors of Ida and Gus. In addition, isolating the polar bears and introducing items may also result in an awareness of each polar bear’s preferred enrichment items. With Gus and Ida competing for the same items, one or the other may not be able to interact with their preferred enrichment item as the other polar bear may possess the desired item.

There are many other methods that can be employed to isolate which enrichment items are most beneficial to the program at the Central Park Zoo. During this study, many different items were placed in the exhibit area without organization or purpose. Controlling the quantity of items placed in the exhibit may show if the polar bears become overwhelmed by too many items in the exhibit or bored if too few are placed in the exhibit area. Gauging the complexity of novel puzzle boxes and tasks can also prove useful. Monitoring can be employed to observe if objects or puzzles with too much complexity frustrate the polar bears leading to stereotypic behavior or if objects or puzzles that are to simplistic lead to increased stereotypic behavior.

All of the data that has been acquired in this study is tentative due to the subjectivity of the collectors. Future studies should maintain a stricter standard of data collecting and collectors should be monitored periodically to ensure that their observations are being recorded in a uniform fashion. Inter and intra observer reliability is critical in a study like this and strict guidelines need to be reinforced. In addition, future studies should be conducted so that evidence can be gathered through time and used to gauge the actual increase or decrease in the stereotypic behaviors of Ida and Gus. The current study relied on anecdotal evidence reported by keepers to determine if the enrichment program is producing marked improvement in the stereotypic activities of Ida and Gus. This is not the best way to quantify the results of a study. To obtain a more accurate estimate of the success of the Central Park Zoo’s enrichment program, the results of future studies should be compared to the results of prior studies rather than on anecdotal evidence.

I also suggest that hormonal changes be monitored closely in the month of February specifically in the first week. The data obtained for this study clearly show a spike Ida and Gus’s activities on February 4th. Perhaps the polar bears are both undergoing a hormonal change that can be detected and monitored or even altered. A hormonal change could be causing a scent or a chemical to be emitted that alerts the polar bears to the onset of breeding season and, in the instance of Gus and Ida, also causes drastic simultaneous changes in their behavior patterns.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for enabling me to conduct this research and for providing valuable insights into the writing of this thesis: John Rowden, Yula Kapetanakos, Celia Ackerman, Ferdie Yau, Bruce Foster, Stephanie Pfirman, Matt Palmer, Ellen Langer, Gareth Russell, Dave Autry, the Central Park Zoo, WCS, and CERC.

References

Altman, Joanne D., “Effects of Inedible, Manipulable Objects on Captive Bears,” Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 2.2 (1999) : 123-132.

Altmann, Jeanne, “Observational study of Behavior: Sampling Methods” Allee Laboratory of Animal Behavior, University of Chicago

Ames, Alison, “The Behaviour Of Captive Polar Bears,” UFAW Animal Welfare

S.C. Amstrup et al., (2001) “Comparing movement patters of satellite-tagged male and female polar bears. Canadian Journal of Zoology 79, 2147-2158.

Beard, Henry and John Boswell. What’s Worrying Gus?: The True Story of a Big City Bear. New York: Villard, November 21, 1995.

Carlstead, K., Seidensticker, J. and Baldwin, R. (1991). “Environmental Enrichment for Zoo Bears”. Zoo Biology 10, 3-16.

Clubb, R. and Mason, G. (2004). Pacing polar bears and stoical sheep: testing ecological and evolutionary hypotheses about animal welfare. Animal Welfare 13, S33-S40.

Coe, J.C., (1985) “Design and Perception: Making the Zoo Experience Real”. Zoo Biology 4, 197-208

Derocher, A. E., Lunn, N. J. and Stirling, I. (2004). Polar bears in a warming climate. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44, 163-176.

Ferguson, S. H., Taylor, M. K. and Messier, F. (2000). Influence of sea ice dynamics on habitat selection by polar bears. Ecology 81, 761-772.

Fischbacher, M. and Schmid, H. (1999). “Feeding enrichment and stereotypic behavior in spectacled bears”. Zoo Biology 18, 363-371.

Debra L. Forthman et al., “Effects of Feeding Enrichment on Behavior of Three Species of Captive Bears,” Zoo Biology 11 (1992): 187-195.

Grandia, P.A., “Stimulating Natural behavior in Captive Bears,” Ursus 12, 199-202.

Greenwald, K. R. and Dabek, L. (2003). Behavioral development of a polar bear cub (Ursus maritimus) in captivity. Zoo Biology 22, 507-514.

Grittinger, T.,”Activity Patterns In Polar bears At The Milwaukee County Zoo.” International Zoo news (1997) 44, No. 2, 68-78.

Hansen, D. J.(2004). Observations of habitat use by polar bears, Ursus maritimus, in the Alaskan Beaufort, Chukchi, and northern Bering Seas. Canadian Field-Naturalist 118, 395-399.

Mason, Georgia J., “Stereotypies: a critical review,” Animal Behavior 41 (1991), 1015 – 1037.

Law, Graham and Kitchener, A. (2002). “Simple Enrichment Techniques for Bears, Bats and Elephants – Untried and Untested. International Zoo News. 49, No. 1, 4-12.

Lyles, Anna Marie; Foster, Bruce and Riffe, Roy. (1997) Polar bear care at Central Park Wildlife Center: Interaction between changing management and behavior , Unpublished.

Shepherdson, D. J., Carlstead, K. C. and Wielebnowski, N. (2004). Cross-institutional assessment of stress responses in zoo animals using longitudinal monitoring of faecal corticoids and behaviour. Animal Welfare 13, S105-S113.

Stirling, I. and McEwan, E. H. (1975). Caloric Value of Whole Ringed Seals (Phoca-Hispida) in Relation to Polar Bear (Ursus-Maritimus) Ecology and Hunting Behavior. Canadian Journal of Zoology-Revue Canadienne De Zoologie 53, 1021-1027.

Ronald R. Swaisgood et al., “A quantitative Assessment of the efficacy of an environmental enrichment programme for giant pandas” Animal Behavior 61 (2001) 447-457.

Mitchell K. Taylor et al., (2001) “Deliniating Canadian and Greenland polar bear (Ursus maritimus) populations by cluster analysis of movements. Canadian Journal of Zoology 79, 690-709.

Wechsler, B. (1991). Stereotypies in Polar Bears. Zoo Biology 10, 177-188.

Wechsler, B. (1992). Stereotypies and Attentiveness to Novel Stimuli – a Test in Polar Bears. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 33, 381-388.